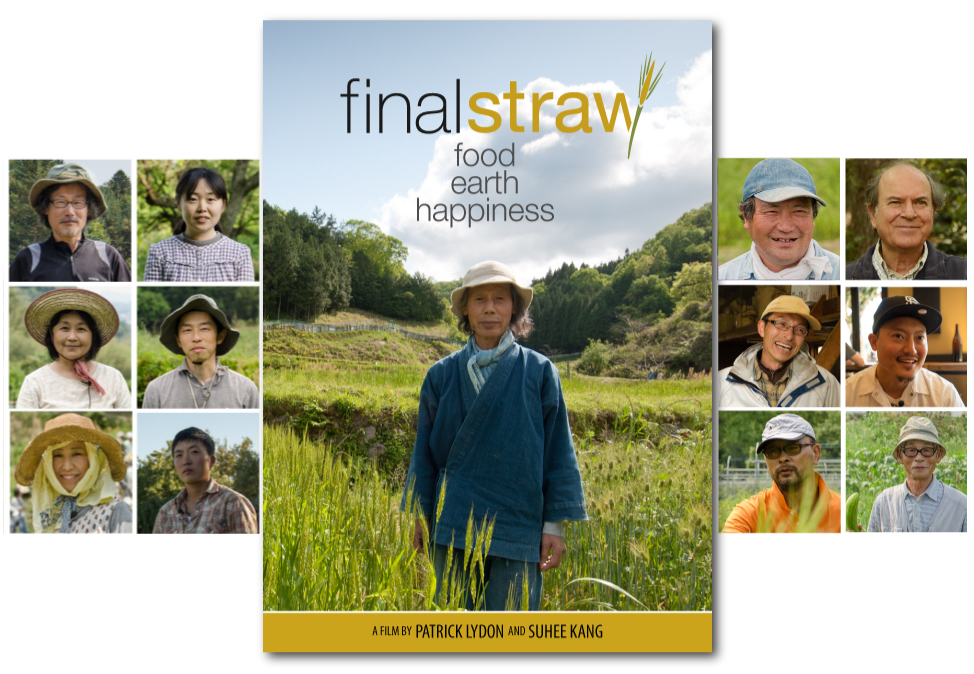

Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness is a documentary by directors Patrick Lydon and Suhee Kang. Filmed over a span of 4 years, they take us to a journey through Japan, Korea and United States to meet many inspiring people: from natural farmers, chefs, and teachers together to discuss critical issues with agriculture and food. The result is a “brilliant yet maddeningly simple path to sustainability and well being for people and the environment” centered around the philosophies of the late Masanobu Fukuoka and his seminal book One Straw Revolution. As we witness in the documentary, this simple path will not only help solve agriculture issue but will help understand more about ourselves and addresses social and ecological issues as well.

We had a chance to discuss with co-Directors Patrick Lydon and Suhee Kang about their project, ideas and future plans.

How did your interest in sustainability issues and natural farming started? How did you came across the book “One straw revolution” by Masanobu Fukuoka and how were you influenced by his writings?

We both grew up in the city, yet were also constantly brought into nature from a young age, so this duality always existed quite strongly in our lives. It lead both of us to be quite critical of our social and economic systems, and as we lived and worked for some years in some of the most fast-paced economies in the world (Silicon Valley and Seoul) we were driven more and more to aim our efforts less at supporting these economies which we saw wrecking havoc in our backyards and further abroad, and instead at finding ways to make these systems work better for people and for nature.

The film itself was inspired by a visit to a natural farmer in South Korea named Seonghyun Choi. At the time, we had just started an online magazine called SocieCity (www.sociecity.org), and we were conducting short interviews with different people and organizations who were building more ecological ways of living; ecological urbanism, economics, and industry.

What Choi demonstrated to us, through his philosophy and way of living and farming, was that all we need to do to solve any of these issues, is to begin building healthy relationships. He was showing how to do this by building a healthy relationship with his land, the plants, his neighbors, customers; the whole system was based on building relationships that enrich the people and places you come into contact with, instead of, as we currently experience, relationships based on economic transactions, monetary profits, and the really disconnected view our society tends to have of endless economic growth. He showed us how everything is connected, and how this view of being connected, and fostering relationships in the transactions carried out your daily life is a key to building social and ecological well being.

After the interview, Choi recommended researching the late Fukuoka-san, and current day natural farming guru, Kawaguchi Yoshikazu. The book “One Straw Revolution” was introduced by him and really opened up the possibilities for us and set the tone for our research and film making. His writings also resonated well with other books we had been reading and thinking on, from economic considerations of E.F. Schumacher’s “Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered” to the poetic prose of Wendell Berry, and more generally, views from Taoist and Buddhist traditions both past and present.

How the idea of documentary came to you and what was the starting point of your work?

It really just started with just that curious interview with Seonghyun Choi, and frustration that in looking for more information about the “natural farming” moment we found very little. Since I had a background in art and photography, and Suhee had a background in journalism and writing, we decided to put our skills together, we knew it had to become a full time project for us, a documentary. We quit our jobs more or less simultaneously, and it all just started falling into place after we made that decision.

During the four years on this project, you worked with many volunteers and collaborators. How did you connect with these people? How did you get to know farmers and activists in Japan, Korea and US who you interviewed?

We just followed the same idea of “cultivating relationships”. I think many film makers tend to feel pressured, whether it’s economic pressure or otherwise, to get funding, build a big team, and to get out there and do the interviews and then come back and edit it all.

For many reasons, we couldn’t do that. Morally we thought we needed to get to know these people, to really understand and live their lives. We also didn’t have funding, just our savings and retirement money, which was not a whole lot. So that dictated how we went about making the film.

The farmers generally responded kindly to our requests to stay with them and learn about what they were doing. A lot of the time, we worked on their farms and got to know them as people, before trying to interview them. I think that helped a whole lot. The interviews became more just like relaxed talks with your mentors, instead of question by question interviews with a stranger.

This way of working also helped open doors to other farmers who might not have talked to us otherwise. Again, that wasn’t the intent, we didn’t have this ploy to work with them so they opened up to us, but rather we just thought to ourselves that this was the best way to know the deeper truths about their ways of living and thinking.

What are the most critical environmental and sustainability issues in your opinion?

I don’t know that there’s so much a ‘critical environmental issue’ as much as a systemic issue of our disconnection from this nature and earth, which is in turn causing countless environmental and sustainability issues, not to mentions social and political ones.

To explain it a bit more clearly, we see the “critical issue” as a disconnection from nature – and by extension from each other. From this disconnection, sprout branches of other issues, economic inequality, social strife, ecological illness.

Our efforts to be sustainable tend to look at these branches, but of course, if a tree is sick, you can just cut off branches, or tie a pretty bow on a branch, you’ve to to address the root issues that are causing this illness.

So we feel that, in order to be truly sustainable, in order to solve the myriad issues of unsustainable life, you can’t just buy the right can of tuna or give money to help starving people. While these are not necessarily bad things, in order for any solution to work broadly and permanently, we have to really tackle the issue of why our way of living causes these issues in the first place. We think these farmers are pretty good at not only talking about that, but also about taking actions that address roots of issues, versus just the branches.

You have been traveling and filming for four years and you have met many beautiful and motivated people. How did you select which stories to include in documentary? What has been left out and if so, do you plan to include those stories in a future project?

The process was one of building a relatively compact story with the most critical bits. After getting the translations back, we pulled out the most critical and powerful ideas and we literally threw them all out on a wall and arranged them. That process itself, funny enough, turned into a gallery show and community engagement project in its own right! We did much of our story development in Edinburgh, and being a very ecologically engaged place like Scotland, we invited some experts and ecology leaders to come by and have a discussion with the community. That process came about through the Art, Space & Nature program at the University of Edinburgh, and it really helped us to frame the story.

In the future, we do plan to include all of the beautiful stories. As may as we can. There’s a lot of extra footage and a lot of it is very compelling. People deserve to see it all, and be inspired by it. Right now it’s just a matter of us being able to devote our resources to it. We’d like to make them all available for free online as short films, releasing them consistently over a period of years.

Starting a “single straw revolution” is a fascinating idea and you believe this can be achieved by people in all countries starting from a small scale. In your movie we have witnessed many examples of people that have changed life style to different extent and “slowed down” to a more natural and low-pace style of living. This could be a difficult challenge for many people, mostly because the modern hectic life style. Where do you think people should start improving their life?

Wherever they can. I think that’s the best place. To look at each action we take, each thing we buy, one by one in our lives. Taking a ‘small actions’ view helps us get our feet wet, because when we look at the big picture and see all the things that are wrong, it often paralyzes us. We feel helpless and we tell ourselves it’s impossible. But it’s not, of course. We just have to start somewhere and not be discouraged. There are more opportunities to change our lifestyles than we see. If we just start looking actively for ways to be more simple, more sustainable, more just, more relationship-based in our dealings with the world, then opportunities come up everywhere.

Of course not everyone is going to accept the prospect of dropping their entire lives to start a small farm, or a small restaurant, or a community-owned business, or some other seemingly large undertaking. Some drastic change.

But we can all make changes in our own actions every day, and as long as we keep pushing at those changes, meeting others who are making changes in their own lives, challenging ourselves each day to live and act in ways we think are moral and just, then we are moving in the right direction.

We just need to start moving, and to keep pushing ourselves each day “doing the right thing and not the easy thing” as the saying goes.

Also, importantly, what ever you are doing, not doing it in isolation. It really helps to be expanding our social circle, and meeting others that are doing intriguing things we want to be doing, it creates mutual inspiration and helps your actions multiply.

Many authors (like Byung-Chul Han in his Fatigue Society) have explored modern man illnesses, such as burnout, depression and other relationship issues. Natural farming is a philosophical theory that in your words “…is not simply about a way of farming to sustain our environment, it was about a way of thinking and being to sustain and nurture all human relationships, ecological and social.” In which way you think this philosophy can help addressing those issues?

Maybe somewhat analogous to Byung-Chul Han’s work is the idea from the natural farmers that we don’t really need to work so hard, to achieve so much, all we really need to do is hang out on the earth, to be here, to live, and to enjoy what nature gives to us. That’s an oversimplification, but he puts into question our need to constantly compete, and to strive for these arbitrary human-defined concepts the “best” or the “most” which, in reality, don’t actually exist.

Because so much of our modern day society is centered around competition, it is extremely difficult to find examples of harmonious relationships in our lives. You can see it by example, in our way of growing food, where we fight against bugs and weeds, and we arrogantly demand that the soil should only grow food for us, and nothing else.

It is actually kind of comical when we think of it, that we demand nature do exactly as we command it. “Don’t provide homes for bugs or microbial life! Don’t grow plants that humans can’t eat! Just grow food!” Of course, nature can’t abide by these demands, and as a result it will either die or retaliate. We examples of both today, the death in our quickly depleting farmlands, forests, watersheds, and oceans; and the retaliation of super weeds and super bugs that nature creates in direct response to herbicide and pesticide use.

This mindset of competition permeates dealings in our daily lives as well, and it serves to make us dreadfully unhappy. Natural farming offers a perfect antidote because it is not based on competition, but on harmony and coexistence. With this mindset, it also doesn’t matter if you are a farmer or not, you can bring such a mindset of coexistence into your actions, into your job, into your relationships with other people, no matter what you do.

“Natural farming” refuses common agricultural practices, such as tillage, use of fertilizer, mechanization and so on. Do you think this is an approach that producers can accept and these changes can also apply to big scale farming?

While there are some common “practices” that seem to be dictated by natural farming, there are truly not any “rules” so to speak. The idea is to have a good relationship with nature, and not to harm it unnecessarily, but instead, to help it flourish. People apply this mindset differently and most natural farmers, while they have their own ways, tend really not to judge those different applications.

In terms of acceptance of the ideas by the current farming population, generally, people will only accept what they can envision. The problem with that and natural farming is that our ability to envision natural farming is limited severely by our current way of doing things, from the way we grow to the way we sell to the way we eat. The entire chain of production and commerce and consumption as we practice and understand it today is fundamentally incompatible with a sustainable future, and consequentially, also incompatible with most natural farming practices.

So there is an issue here that, even if we show a ‘working’ system to conventional farmers, that system really is functioning outside of the “normal” social and economic systems; farmers requiring consumers to visit the farm, for instance, isn’t normal social protocol, but many natural farms ask that of customers. Many farmers can’t envision that, so if they do change, it will still take some time and personal experiences for those farmers to be able to envision themselves doing it.

Storytelling is powerful here, but in the end, I feel that storytelling is the first step, and that the life experience is what changes mindsets. The film in this sense, plants a seed, and it’s up to the people who have that seed to help it grow. We’re thoroughly convinced of the natural farming mindset, we can envision it, but it took us four years of talking and working with these farmers to see that.

Maybe though, with the severely small number of farmers out there, it’s going to be more of a transition in young people choosing natural farming because it fulfills their needs as human beings that are not being fulfilled in their current work life, primarily, the need to be creatively engaged in doing something meaningful. It’s those people who are responding most to the film, and probably, who are going to be the next generation of farmers and artisans and craftspeople and business people who really rebuild the image of society into a sustainable one.

Their website www.finalstraw.org is rich of material for learning more about Natural farming and sustainability. If you want to watch the documentary you can download from their website and make a donation to support their activities here